Talk Test Treat Trace

Chapter 4: Contact tracing

In this chapter

Key points

- Contact tracing is an essential component of case management for sexually transmitted infections (STI) and blood-borne viruses (BBV).

- Effective contact tracing interrupts the ongoing transmission of STIs and BBVs, prevents reinfection and helps to reduce their prevalence in a community in the longer term.

- Both index cases and their contacts should have a thorough history taken and be provided with information, testing and treatment for all STIs and BBVs, not just the one that has been identified.

- How far back to contact trace varies depending on the specific STI or BBV as well as the individual’s history, which may indicate when they were likely infected.

- Contact tracing should be led by the managing clinician; however, other staff, particularly those with local knowledge, can assist to ensure it is done in an appropriate way.

- Priority should always be given to infections that may have significant consequences if not followed up.

- Always contact the regional public health units (PHUs) for advice and assistance with difficult or complex cases.

What is contact tracing and why is it important?

Contact tracing or partner notification is the process undertaken to identify contacts of someone with an STI or BBV, to enable them to access appropriate information, testing and treatment. The person first identified with having an STI or BBV is usually referred to as the 'index case' while 'contacts' or 'partners' refer to those who may have been exposed to an infection.

Contact tracing is an essential component of STI and BBV case management. Effective contact tracing is important to:

- provide information on prevention, harm reduction and the early detection and treatment of STIs and BBVs

- prevent the transmission of STIs and BBVs

- prevent the reinfection of the index case

- reduce the overall prevalence of infections in a community in the longer term.

The index case provides a starting point for contact tracing; however, both index cases and contacts should be managed in the same way with regard to history taking, providing appropriate information, testing and treatment. Be aware that the index cases of STIs such as chlamydia are often first identified among women, simply as a result of women being tested more frequently than men. Thus the index case is not necessarily the person who has ongoing risks for transmission.

Conducting contact tracing can present challenges but it is important to remember the following:

- Effective contact tracing usually involves following up more than one contact.

- The index case may not necessarily have, or disclose, identifiable risk behaviours or be at risk of ongoing transmission.

- Don't make assumptions and be careful not to attach blame to index cases and contacts but do provide accurate information regarding the transmission of STIs and BBVs.

- Both index cases and contacts could be at ongoing risk and should have a thorough history taken and be provided with information, testing and treatment for all STIs and BBVs, not just the one that has been identified.

- Contact tracing should always be conducted in a way that ensures privacy and confidentiality.

- Priority should always be given to infections that are uncommon or that may have significant consequences if not followed up.

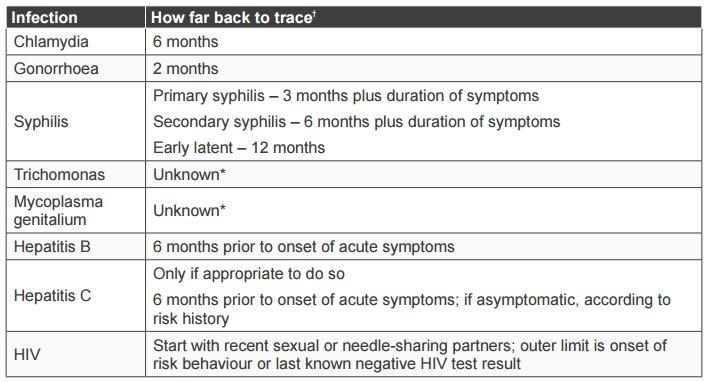

How far back to contact trace varies depending on the incubation and infectious timeframe of the specific STI or BBV, as well as the individual's history or the development of symptoms that may indicate when they were likely infected. Six months is often used as a general guide for how far back to trace; however, as outlined in Table 3 (adapted from the Australasian Contact Tracing Guidelines 2016), this timeframe is variable. Infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may have been acquired years ago and it may take time to develop rapport and gain trust with the index case to provide effective contact tracing and consequently enable contacts to access treatment.

Table 3. Guidelines on how far back in time to trace contacts

Adapted from the Australasian Contact Tracing Guidelines 2016

ϯ These periods should be used as a general guide only: discussion about which partners to notify should take into account the sexual or relevant risk history, clinical presentation and patient circumstances. With regard to hepatitis C and trichomonas, refer to the information provided in this chapter for further guidance.

* There is currently insufficient data to provide a definite period for some infections, although partner notification is likely to be beneficial, is recommended and should be guided by the sexual history.

More information on contact tracing is available in the Australasian and WA guidelines:

http://contacttracing.ashm.org.au/

http://ww2.health.wa.gov.au/Silver-book

Some services, such as the Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Service (KAMS), have adapted or developed these guidelines to provide useful guidelines to contact tracing in the local region. The adapted guidelines are available on their website: https://kams.org.au/

When should contact tracing be initiated?

Contact tracing should be initiated when either an STI or BBV is detected on a laboratory test or on clinical diagnosis when a person presents with signs or symptoms that are likely or definitely due to a STI or BBV.

Symptoms that are highly suggestive of STIs that should prompt the commencement of contact tracing before a test result include:

- urethritis (dysuria or discharge) and epididymitis in men

- symptoms in young women suggestive of pelvic inflammatory disease [PID] (when other causes of low abdominal pain have been excluded)

- genital ulcers suggestive of primary or secondary syphilis.

Contact tracing should be initiated at the time of presentation of STI symptoms. If the diagnosis is not clear, at a minimum, practitioners should advise clients to abstain from sex until the diagnosis can be confirmed, or determined to be likely, due to the history, signs and symptoms, and the exclusion of other causes. Detecting an STI on a laboratory test usually confirms the diagnosis; however, a negative test result does not exclude a diagnosis, particularly in the case of urethritis, epididymitis and PID. Test results are often negative in the context of these symptoms, but other factors such as a rapid response to appropriate treatment and the exclusion of other causes can make the diagnosis likely. Therefore, contact tracing should be initiated on the basis of both laboratory test results and a clinical diagnosis of STI syndromes.

In the context of STI syndromes, do not wait for a confirmed laboratory test result before initiating contact tracing because:

- syndromes are highly suggestive of STIs

- PID, urethritis and epididymitis are clinical diagnoses

- antibiotic treatment is given to cover the most common causes of STI syndromes but only some of those STIs are routinely tested for

- laboratory tests may confirm a diagnosis, but negative laboratory test results are common and do not exclude the diagnosis

- test results may be negative for many reasons such as another causative STI (i.e. testing from the lower genital tract may not detect infection in the upper genital tract)

- failure to treat contacts appropriately in a timely manner leads to a high risk of reinfection of the index case and ongoing transmission to others.

Discussions regarding follow-up and contact tracing should begin at the time of testing for STIs and BBVs; however, the amount of information provided at that time will vary depending on the context and reason for testing. How much information is given at the time of testing may depend on why the person is being tested (asymptomatic screening versus presenting with symptoms), how much time is available, the skills of the practitioner to conduct a detailed discussion, the appropriateness of the practitioner to the client, and the reason for the consultation. Start the conversation by asking permission if it is OK to ask them some more questions and provide them with an opportunity to ask questions about STIs and BBVs.

Index cases and contacts are much more likely to cooperate with the process of contact tracing if they are provided with appropriate information explaining why it is important. At a minimum, at the time of testing for STIs and BBVs the practitioner should:

- briefly explain what tests are being taken and why

- obtain verbal consent to testing

- assure clients of their privacy and confidentiality but also inform them that if an infectious disease is identified, you are required by law to notify the Department's public health department

- provide relevant and current information about the E-Health record with regard to STI and BBV testing

- check contact details and establish the best way to contact them and arrange for treatment in the event that an STI or BBV is detected.

A detailed sexual and risk history should always be taken when someone presents as a contact or with any signs or symptoms of STIs or BBVs. In the context of asymptomatic screening, it may not always be possible or appropriate to take a detailed sexual and risk history at the time of testing; however, if an STI or BBV is detected, a history should be taken at follow-up.

Treatment and follow-up

Contacts should be given treatment as soon as possible, irrespective of whether they have symptoms or not. Explain to the index case the importance of treating their contacts both to avoid reinfection to themselves and ongoing transmission to others. Reinforce the advice that they should abstain from sex until their regular partner(s) has been given treatment plus the time taken for treatment to take effect to avoid reinfection (usually five to seven days). Discuss transmission and prevention of STIs and BBVs and provide information and condoms as appropriate.

It may not always be possible to check whether contacts were treated within an appropriate timeframe; however, it is good practice to ask the index case at follow-up whether they know if their contact(s) were treated in a timely manner, to determine if they have been at risk of reinfection. In the context of symptomatic infections, this should be asked at a follow-up appointment or by a phone call conducted within two weeks of treatment to ensure symptoms have resolved, or at the time of follow-up testing in three months. If a contact of an index case has symptoms or an STI is detected, they should also have a follow-up test in three months or return earlier if they develop any symptoms. People should be informed that a follow-up test is recommended in three months and informed how they will be contacted (such as by SMS or email). You should gain their consent for a reminder to be sent and check their contact details.

How is contact tracing done?

There are many different ways in which contact tracing can be done. Practitioners should provide information and options to individual clients and guide discussions to identify the most appropriate way for them. While it is generally the responsibility of the clinician who ordered the test or who is managing the client to lead the process of contact tracing, assistance can be provided by other staff members. In particular, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health staff often have valuable local knowledge that can assist with guiding how best to conduct contact tracing. Cooperation between various staff members can enable appropriate and effective contact tracing.

Patient referral refers to when the index case (patient) notifies their contacts either directly or indirectly. Patients may choose to inform their contact(s) directly in person, by phone, SMS, email or social media. Practitioners can assist this process by providing a proforma letter that can advise what STI or BBV the patient may have been in contact with, what tests and treatment should be offered and what services they can access. Many services have developed their own templates for letters (such as the template available on the Silver Book website).

Patients may also choose to notify their contact(s) indirectly through websites such as Let Them Know and Better to Know that can send an SMS or email anonymously.

https://www.bettertoknow.org.au/

Provider referral is when the provider (practitioner) notifies the contacts directly or indirectly. Both methods require discussion with the index case to provide information such as the name and phone number of the contacts. In some cases, it may be appropriate for the practitioner to recommend provider referral as the most appropriate way for contact tracing to be done. For example, if HIV, syphilis or resistant gonorrhoea is identified, if a contact is pregnant or if domestic violence is of concern, practitioners may need to seek assistance from their local PHU and inform the index case of the reasons for that approach.

Patient-delivered partner therapy

There are many benefits for contacts to access health services beyond receiving treatment, including being provided with appropriate information, testing for other STIs and BBVs and assessment to determine if other contacts need to be treated. Despite this, it is not always straightforward and contacts may not be willing to attend health services for treatment. Patient-delivered partner therapy refers to providing medication or a prescription to the index case to give to their contact(s) in the event that other ways of treating contacts have failed. While this method of contact tracing is currently not permitted under Western Australian (WA) legislation, Victoria and the Northern Territory (NT) do allow this method for the follow-up of uncomplicated chlamydia infections only. Where it is allowed, it should not be used if index cases have been diagnosed with more than one STI or HIV, if a partner is pregnant or if there is a risk of domestic violence.

When to refer to PHUs or other agencies

Whichever method is chosen, health services and staff have a responsibility to ensure that contacting tracing is undertaken as an integral part of appropriate case management of people with STIs and BBVs. In most instances, it is the responsibility of the managing practitioner (who ordered the test or who is managing treatment or follow-up) who should discuss contact tracing with the index case and the manner in which it can be done. Health services should have clear guidelines regarding roles and responsibilities relating to contact tracing and may have specific staff who can assist with this process, either at the point of discussion with the index case or with the follow-up of contacts.

It is important to note that contact tracing for STIs and BBVs is the responsibility of the managing clinician and health service and not the PHUs. However, on receipt of a notification form, the unit can be contacted to assist with this process. PHUs are an important point of contact for assisting with follow-up of contacts who may be mobile or where the follow-up of contacts is a priority, such as with HIV or syphilis. When a contact is known to live in a different community, the local health service can also be contacted directly to assist. Ideally, PHUs and other health services should also provide feedback to confirm whether a contact was able to be treated or not.

Special considerations

Conducting contact tracing for some STIs and BBVs may require more urgency and should be done more carefully due to the potential for harm to individuals and relationships if not done appropriately.

In the case of HIV, syphilis and antibiotic-resistant gonorrhoea, a notification will trigger the local PHU to contact the service provider to complete the enhanced surveillance form and discuss treatment and contact tracing. With regard to HIV, referral to an HIV specialist will need to be arranged or, if not practical, an HIV specialist can be consulted and assist management in partnership with the local medical officer or health service.

Hepatitis C is not routinely contact traced in WA due to the complexity of issues such as those related to how and when it may have been acquired (e.g. injecting drug use and use of illegal drugs). Despite that, affected people who are current injecting drug users should be encouraged to advise their regular injecting partners to enable them to access testing and treatment.

Regular contacts of young women with trichomonas should be treated to prevent reinfection; however, contact tracing among older women can be complicated by several factors. Unlike chlamydia and gonorrhoea, in communities where trichomonas is common, it is not confined to young age alone, and women can remain infected for years. Among older women, trichomonas is often detected on a vaginal swab or cervical screening, which may not necessarily indicate recent acquisition, but could simply be the first time in years that they have had a test that can detect trichomonas. Women should always be treated and the treatment of their regular partner should be discussed with them. Care needs to be taken that the women and their partners understand that the infection could have been acquired a long time ago. Contact tracing for trichomonas among older women should not be undertaken if there are concerns that doing so will cause harm to the women and their relationships.

As part of good clinical care, your role is to encourage and support your patient in notifying their contacts.

Prioritising cases

Contact tracing can be a time-consuming process, so it is important to understand the occurrence of infections or circumstances that make it appropriate to spend time and resources on contact tracing and when decisions should be made to discontinue trying to follow-up contacts.

Factors to consider when prioritising cases include the following:

- if the infection is serious, such as HIV and syphilis

- if the contact is known to be pregnant due to the potential consequences for both mother and baby

- if the infection is uncommon

- if antibiotic-resistant gonorrhoea is identified.

Healthcare providers have ethical and legal responsibilities for the health and wellbeing of the contacts and/or potential contacts of the index patient. More information about these responsibilities as well as non-compliant cases is described in the Silver Book. The WA Public Health Act 2016 (Division 3, Part 9) has more information regarding ethical and legal responsibilities.

With regard to non-compliant patients, people will usually cooperate if they are provided with information as to why contact tracing is important. Some people may require more time spent with them for counselling. Practitioners need to also be aware of their duty of care with respect to protecting the privacy and maintaining the confidentiality of both index cases and contacts. If you are unsure about any of these issues or have difficult or non-compliant cases, always contact the regional PHU for advice and support.

Deciding when to stop following up contacts

In practice, if contacts are not followed up within a few weeks, they often they get lost to followup, either because health service systems are not robust or because individual practitioners do not follow through with case management. Health services and staff should address gaps in their systems to prevent people becoming lost to follow-up simply because they weren't able to be found quickly.

Some contacts truly are difficult to follow up for a number of reasons, such as contact details are not accurate or current, or contacts refuse to cooperate and don't present to services for treatment. Health services should have made reasonable steps to follow up contacts within their services and by seeking assistance from other services or the regional PHU. Ideally, health services should have a process whereby individual cases are discussed with appropriate staff in collaboration with PHUs and collective decisions are made to discontinue follow-up. If decisions are made to discontinue, there should be clear documentation regarding what attempts have been made to follow up contacts, any correspondence with the unit and the reasons for discontinuing contact tracing.

Documentation and evaluation

While clear documentation regarding attempts to follow up and the timely treatment of contacts is important to assist with continuity of care as well as for medico-legal reasons, it is equally important to ensure that the confidentiality of both index cases and contacts is maintained in this process. While the names of contacts should not be recorded in the index case notes (and vice versa), information can still be documented that clarifies what attempts have been made to follow up contact(s) and if and when they were treated (if known). Many health services maintain a separate, confidential system or register for recording details about contact tracing. Evaluation of contact tracing may differ between health services but should focus on the timeliness of treatment and the proportion of contacts successfully treated. As part of the national response to the syphilis outbreak, PHUs in affected regions report against two key performance indicators (KPIs) to the Multijurisdictional Syphilis Outbreak working group (MJSO).